Mark Frauenfelder, writing in his newsletter The Magnet, tags this “the most interesting psychiatric case in history”. As a clinical psychiatrist I’m not sure I would be quite so ebullient, but I have a similar love for and fascination with this 1955 account by psychoanalyst Robert Lindner (1914-1956) of his pseudonymized treatment of a physicist, referred to as Kirk Allen and likely someone who worked at Los Alamos and made important contributions to the Manhattan Project during WWII. I was fairly certain that I had written about ‘The Jet-Propelled Couch’ here on FmH but a search back reveals not.

Allen’s supervisors, observing his erratic behavior and preoccupation on the job, had sent him for psychiatric evaluation and Lindner found that he had an elaborate fantasy life in which he could teleport back and forth between his earthly existence and a life in a part of the universe distant in time and space in which he was the lord of an interstellar empire. Allen kept meticulous notes of his adventures which he shared with Lindner, running to 12,000 pages of manuscript complete with notes, extensive glossary, maps, chronologies of the history of the planet over which Allen ruled, and hundreds of drawings he had made of aspects of alien life.

Lindner ran the gamut of conventional treatment approaches of the day in trying to cure Allen of his delusion without success. Then, he describes having the “sudden flash of inspiration… in order to separate Kirk from his madness it was necessary for me to enter his fantasy and, from that position, to pry him loose from the psychosis.” Lindner joined in Allen’s fantasy life with enthusiasm and wrote of his growing relish for and obsession with his patient’s adventure stories. He encouraged Allen to return to his other life repeatedly, awaiting their sessions with impatience to hear about Allen’s further exploits on alien worlds. Little by little, however, in what I find the most fascinating aspect of the story, he began to note Allen’s growing discomfort with his coaxing until Allen reluctantly confessed that for several months he had no longer believed in the reality of his stories. He had realized he had been delusional but had continued faking it because he did not want to disappoint his fascinated psychoanalyst. Lindner wistfully mourned the loss of what had been such a passionate fantasy for himself. He was humbled and abit shocked by the ‘there-but-for-the-grace-of-God’ blurring of the distinction between therapist and patient he had experienced in his treatment of Allen.

I have long used this vignette in teaching my students and trainees about the complexities and pitfalls of treating people with the difficult and challenging beliefs referred to as “delusions”. As an analyst* Lindner could not have been expected to have facility dealing with delusions. Patients with psychotic symptoms were, and are to this day, rarely if ever seen on the psychoanalyst’s couch. Those of us who treat patients with this degree of dysfunction more regularly understand that there is a much more complicated dance, rather than a simple black or white dichotomy, between combatting and joining in the delusions. And similarly the goal of treatment is much more complex and nuanced than a “cure” in which the patient gives up the “unfounded” beliefs and is restored to “reality” or “normalcy”. Through the medium of the relationship with their treater (which I am alarmed to see is seen as a deprecated part of psychiatric treatment in the current medication-centric era of treatment), patients can be helped to move toward a more comfortable degree of joining in the consensus reality of their social group and culture, as they choose.

As Lindner’s case study illustrates, one of the ways to grapple with psychiatric symptoms is to understand them as serving a purpose in their bearer’s life. Delusional systems can actually be thought of as theories the patient has constructed to reassure and comfort them by helping them understand otherwise inexplicable and alarming aspects of their mental and emotional functioning. Even when no longer believed, such a theory or worldview may continue to be enacted or expressed by a patient for various reasons, such as to save face or avoid a breach in an important relationship, as in Kirk Allen’s case. The student should learn to grapple with the complexities embodied in every such symptom and what we call “countertransference,” the effects of the treater’s own often unconsciously motivated attitudes toward and reactions to what their patient is telling them.

Frauenfelder goes on to dissect the effort that has been given to figuring out who Kirk Allen really was, as Lindner had taken the secret to his grave, dying a year after the book’s publication. Lindner’s case study explained that, as an escape from his childhood unhappiness, Allen had read and reread a series of science fiction novels he found in the library starring a protagonist supposedly sharing his name, a takeoff for fantasizing about additional adventures starring his namesake. As a science-fiction fan myself, when I first read the Lindner essay I shared the feeling of many that Allen’s adventures smacked of Edgar Rice Burroughs’ John Carter of Mars series. However, a scientist named Carter working at Los Alamos could not be identified and, after spending many years trying to figure out who Kirk Allen was, biographer Alan Elms** published a piece in 2002 in the New York Review of Science Fiction arguing that the science fiction writer Cordwainer Smith (pen name of political scientist and psychological war expert Paul Linebarger) was a more plausible choice, despite the fact that no one named Linebarger featured as protagonist in a science fiction series from that time.

Frauenfelder goes on to dissect the effort that has been given to figuring out who Kirk Allen really was, as Lindner had taken the secret to his grave, dying a year after the book’s publication. Lindner’s case study explained that, as an escape from his childhood unhappiness, Allen had read and reread a series of science fiction novels he found in the library starring a protagonist supposedly sharing his name, a takeoff for fantasizing about additional adventures starring his namesake. As a science-fiction fan myself, when I first read the Lindner essay I shared the feeling of many that Allen’s adventures smacked of Edgar Rice Burroughs’ John Carter of Mars series. However, a scientist named Carter working at Los Alamos could not be identified and, after spending many years trying to figure out who Kirk Allen was, biographer Alan Elms** published a piece in 2002 in the New York Review of Science Fiction arguing that the science fiction writer Cordwainer Smith (pen name of political scientist and psychological war expert Paul Linebarger) was a more plausible choice, despite the fact that no one named Linebarger featured as protagonist in a science fiction series from that time.

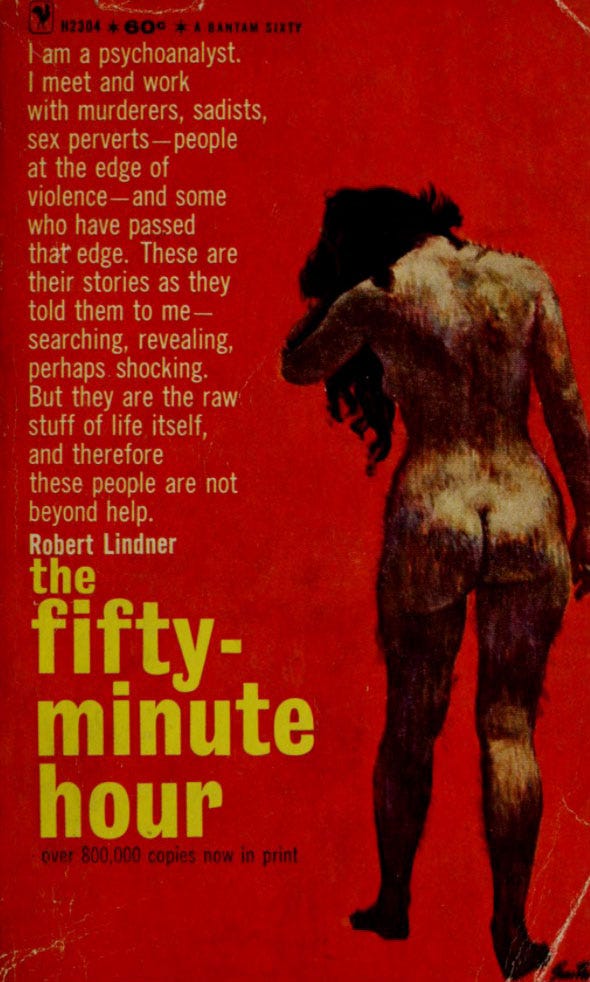

‘The Jet-Propelled Couch’ is available to read here in a Harper’s Magazine archive from 1954. The Kindle edition of The Fifty-Minute Hour can be obtained here. (‘No student’s education in psychotherapy is complete without reading this book.’)

*a practitioner of classical psychoanalysis based on “analytic neutrality” and facilitating insight via interpretation of the patient’s unconscious conflicts through free association, fantasies, and dreams. Generally occurring in 50-minute sessions multiple times a week and, typically, with the patient or analysand lying on a couch with the analyst just behind and out of sight.

**As Frauenfelder points out, Elm was coincidentally the research assistant to Stanley Milgram on the famous electric shock experiment on obedience to authority.